In 1956 Calvino published a seminal collection of Italian folktales.

#Italo calvino tarot series

Sponsored by Elio Vittorini and published in a series of books by new writers called Tokens, it was immediately praised by reviewers, though its departure from the more realistic style of his first novel resulted in criticism from the party, from which he resigned in 1956 when Hungary was invaded by the Soviet Union. Calvino joined the Italian Communist Party and reported on the Fiat company for the party’s daily newspaper.Īfter the publication of his first novel, Calvino made several stabs at writing a second, but it was not until 1952, five years later, that he published a novella, The Cloven Viscount. In the postwar period the Italian literary world was deeply committed to politics, and Turin, an industrial capital, was a focal point. When The Path to the Nest of Spiders appeared in 1947, the year that Calvino took his university degree, he had already started working for Einaudi. The novel did not place in the competition, but the writer Cesare Pavese passed it on to the Turin publisher Giulio Einaudi who accepted it, establishing a relationship with Calvino that would continue throughout most of his life. During this time he wrote his first novel, The Path to the Nest of Spiders, which he submitted to a contest sponsored by the Mondadori publishing firm. He published his first stories and at the same time resumed his university studies, transferring from agriculture to literature. When the Germans occupied Liguria and the rest of northern Italy during World War II, Calvino and his sixteen-year-old brother evaded the Fascist draft and joined the partisans.Īfterward, Calvino began writing, chiefly about his wartime experiences. The future writer studied in San Remo and then enrolled in the agriculture department of the University of Turin, lasting there only until the first examinations. As Calvino grew up, he divided his time between the seaside town of San Remo, where his father directed an experimental floriculture station, and the family’s country house in the hills, where the senior Calvino pioneered the growing of grapefruit and avocados.

Shortly after their son’s birth, the Calvinos returned to Italy and settled in Liguria, Professor Calvino’s native region. Calvino’s mother Eva, a native of Sardinia, was also a scientist, a botanist. His father Mario was an agronomist who had spent a number of years in tropical countries, mostly in Latin America. Italo Calvino was born on Octoin Santiago de Las Vegas, a suburb of Havana.

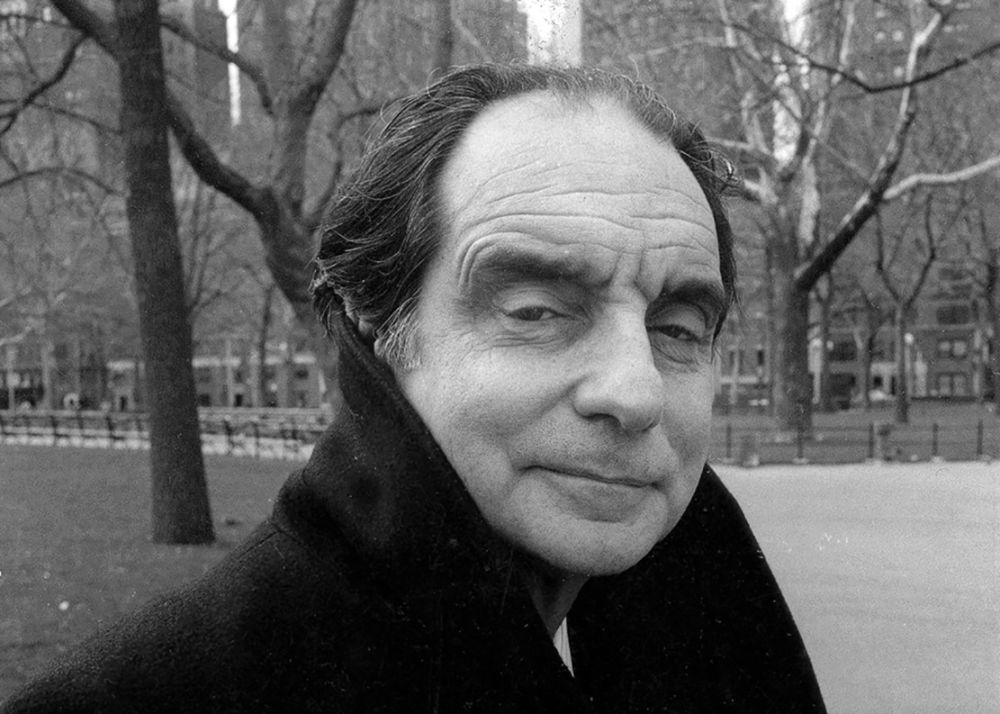

What follows-these three selections and a transcript of Calvino’s thoughts before being interviewed-is a collage, an oblique portrait. Still later, The Paris Review purchased transcripts of a videotaped interview with Calvino (produced and directed by Damien Pettigrew and Gaspard Di Caro) and a memoir by Pietro Citati, the Italian critic. It was never completed, though Weaver later rewrote his introduction as a remembrance. Two years before, The Paris Review had commissioned a Writers at Work interview with Calvino to be conducted by William Weaver, his longtime English translator. He took fiction into new places where it had never been before, and back into the fabulous and ancient sources of narrative.” At that time Calvino was the preeminent Italian writer, the influence of his fantastic novels and stories reaching far beyond the Mediterranean. Upon hearing of Italo Calvino’s death in September of 1985, John Updike commented, “Calvino was a genial as well as brilliant writer. Interviewed by William Weaver & Damien Pettigrew Issue 124, Fall 1992

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)